Personal data beginning to feel less sinister

/The mood about data has shifted, an article in the Atlantic written by Jacoba Urist published yesterday, signals the change. Personal data has been something to hide, to fear and worry over privacy...but now it's viewed as a commodity, fodder for art making. Location, steps, heart-rate, spending, clicks, likes are the medium, the material for art. To me, it feels like the world is catching up. Data has become the new medium for art makers. If art reflects the times, the way data artists are responding and using data gives us a clue how this moment of personal data invasion will be seen in ten or twenty years. Watching what artists do now will let us see the future. And the future of data is positive, I absolutely think it will be the source of self-knowing. As Jacoba writes, a high-resolution view into yourself.

Excerpts from the incredibly well argued and written article from Jacoba Urist.

"A number of artists, scholars, and curators also believe that working with this data isn’t just a matter of reducing human beings to numbers, but also of achieving greater awareness of complex matters in a modern world. Art confronts the uncertainty of human existence: Why am I alive? What makes me different from anybody else?Handprints made some 40,000 years ago, are a common feature of Upper Paleolithic cave art—a kind of prehistoric selfie. National Geographic describes the early artists as sending a timeless message: “Like you, I am human. I am alive. I was here.”

So it’s unsurprising that many data artists are responding to an increasingly data-saturated culture. After all, almost every human interaction with digital technology now generates a data point—each credit-card swipe, text, and Uber ride traces a person’s movements throughout the day. The smartphone, as The Economistrecently described, is a true personal computer, the defining innovation of the era, on par with the mechanical clock or the automobile in past centuries."

“Have you ever thought about how much is known about you?” Frick asked in one of our conversations. Not what pops up in Google or on social media, she clarified, but what companies know about your character. If you have a Kindle, Amazon knows how fast you finish a book, and whether you’re a cheater and skip chapters or read the ending first. Netflix knows whether you’re a binge watcher. E-ZPass knows where you go, even on local streets. Frick understands that this type of data collection can cause discomfort. Few of us like the idea that the government or Google is watching our every move. As a data artist, however, she sees her role as convincing people to want more personal data—regardless of who’s tracking.

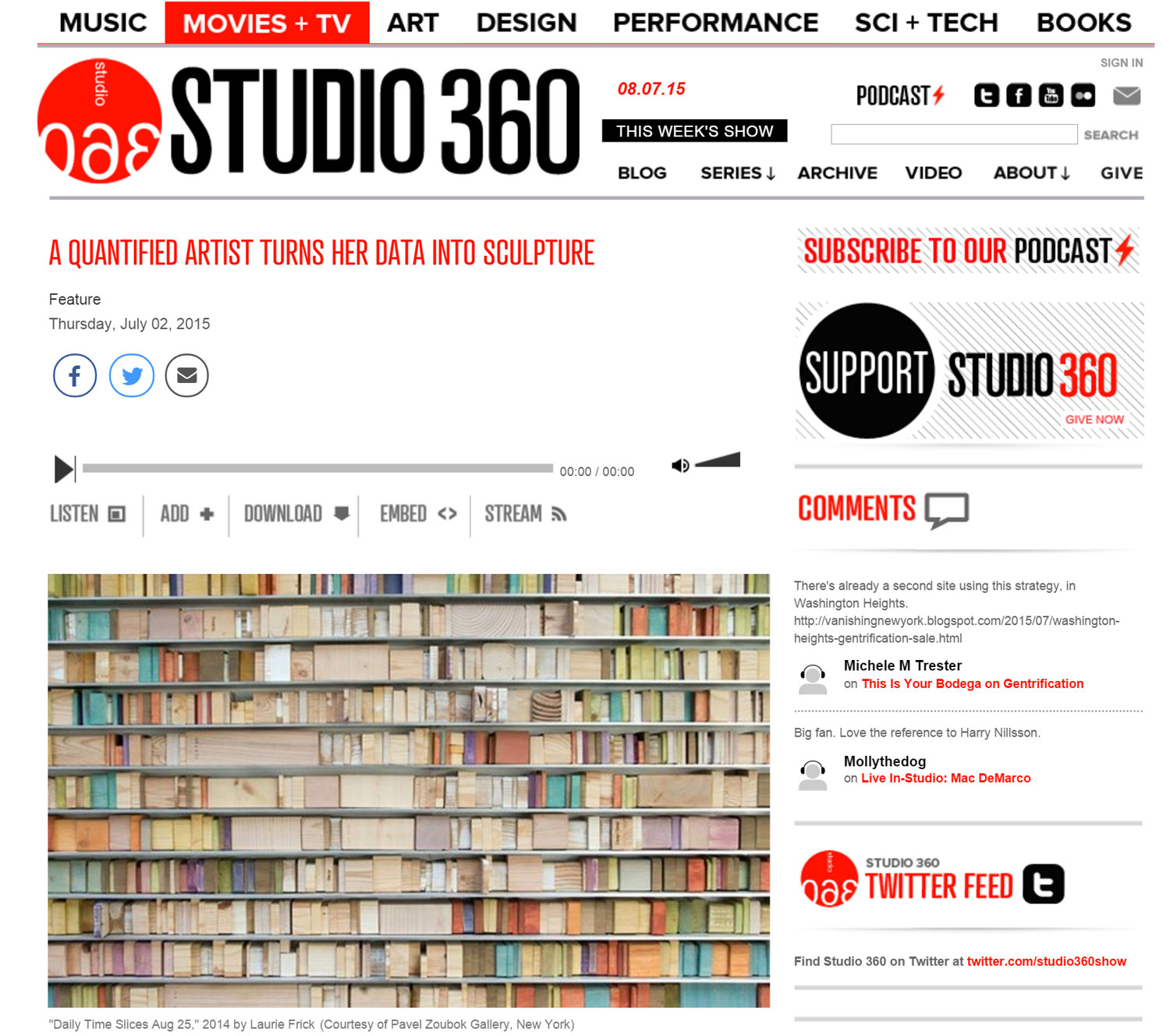

“In all of these patterns, I do think there is an essential idea of who we are,” Frick said. Data art can’t capture the essence or totality of somebody—if either exists—any more than a handprint on a cave wall can. But she believes personalized data art can accomplish something traditional art forms can’t: It allows a viewer to see her nuances and idiosyncrasies in higher resolution—and to discover things she may have forgotten about herself or perhaps has never known. “I think people are at a point where they are sick of worrying about who is or isn’t tracking their data,” said Frick. “I say, run toward the data. Take your data back and turn it into something meaningful.” To prove her point, she’s developed a free app, Frickbits, which allows anyone to “create the ultimate data-selfie,” by turning personal data into personalized art.

"Yet the question remains whether data art can endure as much as a simple, striking handprint on a cave wall. On the one hand, data art may just be a link in a chain of artists who record and display their personal movements— some of whom will be displayed at the world’s leading museums decades from now, some who will fall by the wayside. On the other, data art may be the apogee of self-expression—a digital fingerprint that says more about modern man, and the inevitable forward march of time, than anything artists have been able to produce before."